How Extortion By INEC Officials, Insecurity Mar Voters’ Registration In Niger Villages

207 Views

24 Aug 24, 2022

Marred by insecurity and extorted by INEC officials, communities in Niger State faced double jeopardy: pay ransom to kidnappers and bribe INEC officials to get PVCs. WikkiTimes’ YAKUBU MOHAMMED documented the travails of residents of some communities in the insurgents’ ravaged Niger State where some officials of the Independent National Electoral Commission were found to be extorting as high as N50,000 per polling unit to register just 30 voters.

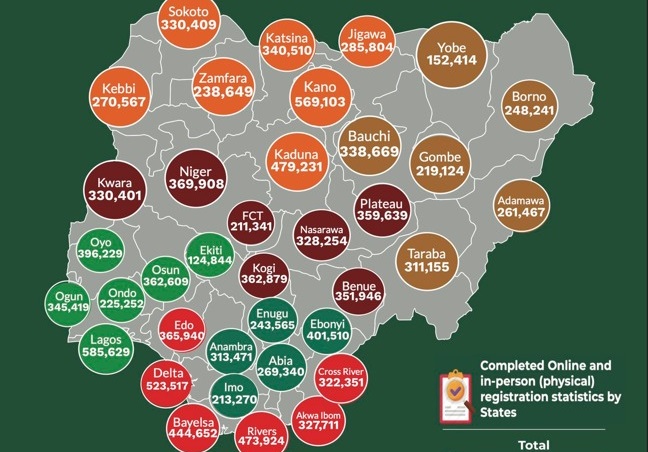

Ahead of the 2023 general elections, Niger State has recorded the largest number of new voter registrations in the North Central region. By August 1, 2022, a total of 369,908 registrations have been completed, according to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC).

The state now has 1.7 million registered voters out of an estimated 4 million population.

Despite this achievement, participation in rural and insecure areas is typically low. WikkiTimes found that many potential voters were unable to register in local communities that had been under attack by terrorists.

Due to the insecurity, WikkiTimes found that some INEC registration agents asked potential voters to pay before registering them.

In Gogata village, four different groups had to contribute N10,000 each to get their people registered. The group namely Soko Majin, Ebo Soko, Soko Deke and Bawu Soko collectively raised N40,000 for INEC officials in Kutigi, the headquarters of Lavun Local government Area.

Despite that, only a few people were registered. “They were not up to 50,” said Mohammed Gogata, the spokesman for Bawu Soko group. According to him, many people were not registered as they were told that their details had already been captured in the system.

In Ndaruka village, residents told WikkiTimes that they contributed N50,000 for the INEC registration agents to carry out the exercise.

A youth leader in Ndaruka, Yakubu Abdullahi said the N50,000 could only register about 30 villagers. “They told many of us that we don’t need a new PVC (permanent voter’s card) since some of us have the ones from 2004, 2007, 2011 and 2015,” he said.

Ndace Abudullahi Ndaruka said he travelled about 30 kilometres to Kutigi after losing his 2015 PVC. “All four times I went there, I would only meet the guard of the facility,” he said. “They are always not around. Luckily, I was captured after we paid for them to come to our village.”

The exercise was similar in other villages, such as Santali, Ebbo, Makolo, Dagbegi, Dagbeko, Ggbacita and Shaku.

Extorting locals has become a norm in Lavun, according to Abdullahi Mohammed Eginda, the Chairman of Lavun Youth Congress (LYC). Corroborating WikkiTimes’ findings, he said LYC has received reliable reports of bribery and extortion in almost every village in Lavun.

According to him, the problem is not peculiar to Lavun alone, but to the whole of northern Nigeria. “INEC asked their staff to go to ward centres where villages under the ward are expected to come there and register,” he said. “For Instance, Egbako is the only ward centre in Nigeria that is not connected to the national grid and when INEC asks their officials to go there, they won’t provide them with logistics?”

The LYC Chairman further noted, “In places where we have mass voters’ registration, it is through the efforts of the villagers who paid INEC officials to get them down to their communities.”

Extortion in Lapai

Just like Lavun, INEC agents deployed to Lapai made bribery a prerequisite to get locals registered.

Kuchi-Kebba and Katakpa villages under Ebbo/Gbanciku ward were asked to raise N50,000 each for the officials, WikkiTimes reliably gathered.

Amid hunger and poverty ravaging locals in Katakpa village, each villager was asked to contribute N200 towards the N50,000 for the registration agents.

“But we were able to gather N30,000,” said Muhammad Shuaibu, a resident of the village. He disclosed that despite this, the officials did not show up, perhaps because “the money was not complete”.

“They asked each villager to pay N200 before they could come and register us,” said Ahmed Mamman, a resident of Katapka. His claim was corroborated by Rabiu Abubakar, the Chairman, Katakpa Youth Must Grow Association. According to Abubakar, more than half of Katakpa residents do not have PVC.

Ahmed Mamman

Residents in Kuchi-Kebba told WikkiTimes that a grassroots politician had to pay to bring INEC officials from Minna, the state capital, to carry out the registration in the community.

Preventing low voter turnout

Fewer than one million voters cast their ballots in the 2019 gubernatorial election in Niger State but as the 2023 election approaches, some youths in Lavun are trying to mobilise more voters.

“Now, we don’t want it to be business as usual,” said Yakubu Abdullahi, a youth leader in Ndaruka. “When you look at our population, we have a lot of unregistered eligible voters who have not been voting simply because they do not have PVC and cannot travel those lengthy kilometres to Kutigi.”

He continued, “In the past, when it is election time, only a few people who had PVC will vote and the rest whose details are on the system but have misplaced their cards will create room for votes not cast. This time around, we want to vote and that is why we are doing all we can to get our people registered.”

Yusuf Saidu, the village of Kurebe

“In the past when there was peace, INEC officials found it easy to get down to our community but not now when the village has been ransacked by criminal elements,” Saidu said, adding, “There are plans to move us to a safer place where we can vote.”

He, however, explained that many of his subjects are not talking about elections again, but security. “Let the government get rid of those terrorists to allow us to have peace in our village.”

This is contrary to a statement by Yakubu Mahmud, the commissioner of INEC who repeatedly said concerted efforts were taken to ensure smooth electioneering procedures in hard-to-reach communities including those troubled by insecurity.

Wasiu Abiodun, the Niger State Police Public Relations Officer (PPRO) declined to comment on the commissioner’s claim to engage security agencies in ensuring those in vulnerable communities were not neglected.

Sani Yusuf Kokki, the co-convener of Concerned Shiroro Youths, in an interview with WikkiTimes explained that some wards would be moved to safer places to exercise their civil rights.

“There is no way INEC will send its officials to some troubled areas. It is not possible,” Kokki said. “I have not confirmed it officially though, but I learnt that people in some troubled areas would be moved to their local government headquarter in Kuta, and other safer places.”

Nonetheless, there are troubled communities that are relatively peaceful at the moment, according to Kokki.

“For instance, villages under Gurmana ward are safe now because of the ongoing construction of Zungeru dam,” Kokki said. “Due to the construction, water has surrounded the whole place and it makes it difficult for bandits to strike.”

INEC commissioner evades interview

For two consecutive days, our reporter visited the INEC head office in Minna, Niger State. But attempts to meet with the Resident Electoral Commissioner, Professor Samuel Egwu were fruitless.

Last month, our reporter alongside three other broadcast journalists were denied access to Egwu. According to them, his retirement is in view and he may not be privileged to speak to the press as he was busy with several official meetings.

The following day, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) Commissioner representing Niger, Kogi and Kwara States in North Central Nigeria, Professor Mohammed Sani Adam, addressed journalists at the commission’s office in Minna.

From left: Resident Electoral Commissioner, Professor Samuel Egwu and Professor Mohammed Sani Adam, INEC Commissioner representing Niger, Kogi and Kwara States, during a press briefing with journalists in Minna on July 26, 2022

Adam, however, dodged salient questions and summarily noted that all the challenges that have to do with local communities have been handled by the commission.

“We have taken care of disjointed and displaced communities,” he said. “That is not a problem as far as INEC is concerned.”

Briefly, after the media chat, WikkiTimes’ reporter met with the resident electoral commissioner, Egwu, who stylishly declined an interview session.

“Not now, please,” he told our reporter. “I have other issues to attend to. Maybe some other times.”

This report was published with support from Civic Media Lab