Untold Story of Almajiri Schools Left For Ruins In Bauchi

272 Views

20 Jan 20, 2024

Over a decade after the Federal Government constructed and handed over Tsangaya Model Schools to SUBEB in Bauchi, Falasa uncovered that Almajiri pupils grapple with hunger and labour as proprietors struggle to meet their needs.

Abdulmalik Umar, a 14-year-old native of Zaranda-Gari, Toro local government area, Bauchi State, enrolled as an Almajiri. He was seeking Qur’anic memorisation at Tsangayar Alarama Malma Mato Gumau, one of the Model Tsangaya Schools constructed in the state under the initiative of the Federal Government in 2012.

Umar, who now lives about 55 kilometres (km) away from his parents, has his teacher, Alaramma Mato Gumau, assuming guardianship and providing for all his necessities for survival.

The young Almajiri wakes up every day filled with uncertainty about how and where he will get meals for the day. This is because, at the moment, his teacher could not afford to provide him with a meal three times a day. This struggle has been one of his worst nightmares since his admission into the school three years ago.

Alaramma Gumau could only offer breakfasts to Umar and his fellow Almajiris. To meet his daily food demands, he patrols streets and houses in Gumau to beg for lunch and dinner. The act has become inevitable to avoid staying hungry for the rest of the day.

“My Tsangaya teacher provides me with only breakfast every day. He gives me a cup of pap in the morning, after which I have to beg to get what I can eat for lunch and dinner,” he said.

When this reporter visited Tsangayar Alaramma Mato Gumau in August 2023, Umar and three other Almajiris were just returning from commercial farm labour. The young Almajiris appeared dirty and exhausted. The farm remained their source for survival after their regular child labour.

Another young Almajiri, Huzaifa Usman, who appeared to be in his mid-teens, told Falasa that they worked as a group on farms in the community every day, especially during the rainy season, after a similar work on the farmland of their teacher.

“We went to our teacher’s farm in the morning, and now, as you see us, we are just returning from paid labour. This is how we make money to meet other demands of life here. We are not with our parents, and they barely send us anything,” Usman said.

According to him, other Tsangaya pupils who were older travelled to other locations for a similar trade, saying, “They would not resume until after harvest.”

Background

The Federal Government (FG), under former President Goodluck Jonathan, allocated N15 billion for the construction of 157 Model Almajiri Tsangaya Schools across the country. The strategy aimed to integrate Western education into the Tsangaya System, empowering children in these schools and addressing the issue of out-of-school children.

The initiative also sought to combat street begging by Almajiri children under the guise of seeking Qur’anic education. The schools got modern state-of-the-art facilities to accommodate pupils and were handed over to proprietors.

According to the initial agreement, the State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB) in each of the 36 states of the Federation would assign and pay teachers responsible for teaching Western Education to the pupils, providing stationeries, and handling feeding.

Tsangaya School, an informal institution teaching children of school-age memorisation and scripting the Holy Qur’an under the guidance of a Malam – teacher.

As a result, constructed Tsangaya Model Schools, domiciled mostly in northern states, continue to waste while millions of children in the region unabatedly account for the chunk share of out-of-school children in the country.

The attitude of parents and guardians who shy from bearing the full financial responsibility of educating their wards enrol children in Almajir schools in faraway locations under the guise of empowering them with the knowledge of the Holy Qur’an. Oftentimes, those parents do not make provisions for either the welfare of the children or their teacher who naturally becomes the new overseer of children placed under him.

A 2022 UNICEF data ranked Bauchi as the state with the highest number of out-of-school children in Nigeria, estimated at 1.2 million. Surprisingly, the children referenced are Almajiris, the age group targeted by the FG’s huge intervention.

Bauchi State received its share of the initiative with 9 Tsangaya Almajiri Model schools constructed and handed over to their proprietors across the state.

But findings by Falasa revealed a failure of the State’s SUBEB, despite being the supervising agency. has seemingly abandoned its responsibilities. The board neither posts teachers nor provides feeding to the Almajiris admitted into the schools, leaving them hungry and destitute.

Alarama Gumau Only Offers Breakfast to Pupils

Alarama Mato-Gumau, the proprietor of Tsangayar Alaramma Mato Gumau, provides only breakfast to 62 admitted Almajiris.

“I do this from my efforts,” he told Falasa . “The pupils beg to scout for lunch and dinner, which is not always handy. On dry days, the students go to bed on empty bellies.”

Field findings revealed that at the inception when government support was forthcoming through SUBEB, the proprietor provided every child with meals three times a day. To a large extent, it discouraged the pupils from begging. Instead, they concentrated on their studies.

Feeding the Almajiris becomes extremely arduous for Gumau without government intervention because the number of pupils is relatively high. To provide three square meals to the children, he claimed that he spends an average of N51,700 daily. Breakfast gulps N12,800; lunch N19,450, and N19,450 for dinner. Monthly, the school spends about N1,551,000.

Similarly, the school lacks the adequate manpower needed to cook the food. Out of the four chefs SUBEB previously recruited to cook for the school, only two remain. The proprietor pays their salaries.

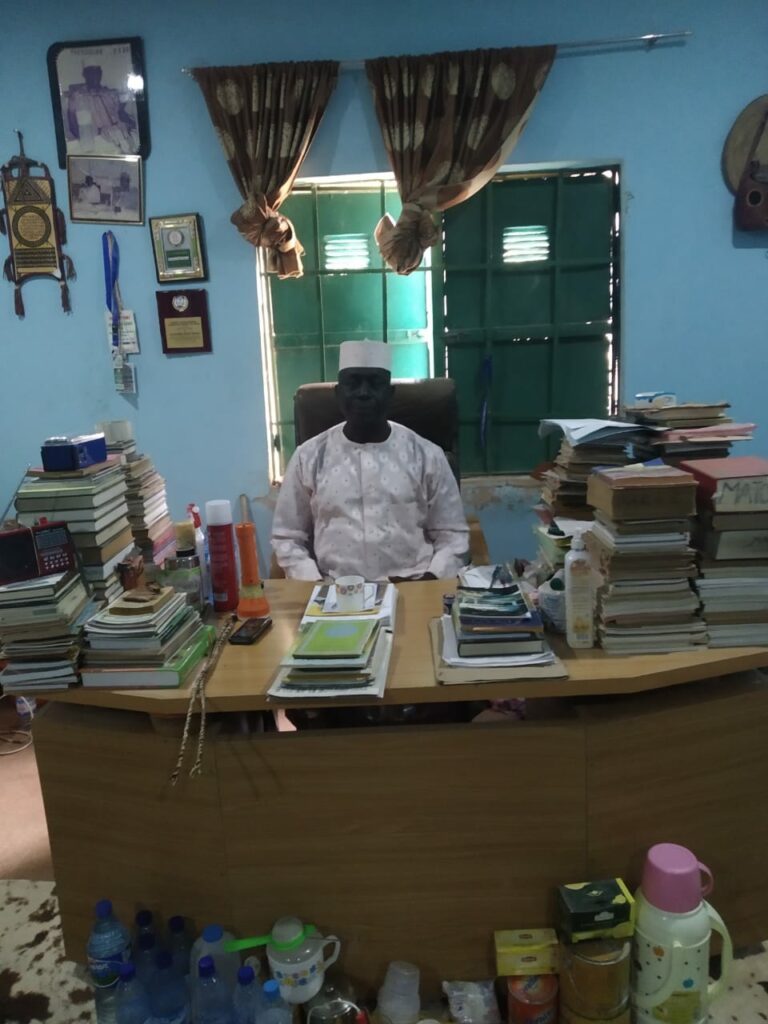

Umar Zakariya Gumau, Headteacher of Tsangayar Alaramma Mato Gumau, told Falasa that the management of the school made provision for breakfast for the children.

“We are able to feed the pupils once because we farm. Sometimes, we give them a pap with Akara or Chin-Chin. It has been a while since we stopped giving them food three times a day,” he recalled while nodding his head to show affirmation.

Abdulrashid Zaranda-Gari, a pupil in the school, narrated that he begs for food from houses in the inner Gumau town to get lunch and dinner.

“Sometimes I don’t get anything. I have to pass the night with hunger. And, as such, I cannot concentrate on my studies,” he said.

Despite The Odds, Gumau Graduates Excel

Following the integration of Western education into Qur’anic Tsangaya schools, Tsangayar Alarama Mato Gumau has produced students who became nurses and teachers.

Falasa ’ findings show that some graduates of the school are enrolled in various tertiary institutions in Bauchi, neighbouring Jos, and other parts of the country, seeking additional education at a degree level after memorizing the complete Qur’an. Additionally, other graduates of the school are currently at the secondary school level.

For instance, the current headteacher of the school, Malam Zakariya, completed his primary education and Qur’an memorization before acquiring a National Certificate of Education (NCE) to become a professional teacher.

“As you can see, I am the school headteacher and also one of its graduates. I can recite the complete Qur’an by heart and write it well. I was one of the first set of students of Alarama Gumau to be integrated into Western education, and here I am today,” he said, pointing to his chest to show satisfaction and accomplishment.

Another graduate Abdulmalik Gumau is a regularized nurse after acquiring a diploma in nursing. Determined to give back to his community, Abdulmalik returned to his native Gumau and established a pharmaceutical store.

Similarly, Aisha Alhassan, 16, one of the graduates of Tsangayar Alarama Mato Gumau, proceeded to secondary school after completing primary education along with memorization of the Qur’an. Currently, she is in SSII.

To Aisha, who wants to become a gynaecologist, enrolling in Tsangaya school, like that of Gumau provides an enabling environment for every child to actualize their dreams – memorizing the Qur’an and accomplishing great things in Western education.

“I was enrolled in the science class because I want to become a gynaecologist. I was taught science right from time in the model Tsangaya school Gumau. Our teachers were very supportive and accommodating to motivate us to aspire to good things in life,” she said.

Aisha was not disturbed being a girl because it is rare to see girls enrolled in Tsangaya schools in northern Nigeria, where the practice exists. However, she was motivated by a burning desire to pursue a medical career.

Data obtained from the office of the proprietor of the school indicate it has five teachers, including the headteacher, who are teaching in the formal education section of the school. They all possess NCE, which is the minimum requirement allowed by Nigerian law to teach.

Ningi Model School, Tsangaya Not Put To Use, Burgled

Tsangayar Alarama Gundumar Kafin-Lemu Ningi was one of the 9 Tsangaya Model Schools the Federal Government constructed in Bauchi state. It was designed to offer basic education and Qur’an memorization to prospective Almajiris while shielding them from street begging.

However, the structure was never used years after it was constructed. The school has remained inaccessible due to overgrown weeds, inviting cattle and other ruminants to graze.

As a result, facilities within the school were stolen, rendering it counterproductive.

Falasa findings indicate that ceiling fans, doors, windows, and furniture installed in the school have been stolen. Similarly, the wind blew off the roof of some classes with tall grass growth, indicating that the proprietor has not put the structure to use yet.

“We have packed the materials left in the school to a secure place to avoid losing everything to thieves who are determined to take away almost everything.

“Initially, a watchman was hired to keep vigilant around the school and its facilities, but we cannot afford to keep paying him salaries monthly. He left,” Yunusa Liman, one of the volunteer Tsangaya teachers working with the proprietor of the school, narrated.

Stakeholders of the school are desirous of a change – to get the school to operate in line with its founding creeds – but Liman argued that all attempts to draw the attention of relevant education authorities at Ningi Local government and Bauchi State Universal Basic Education Board were unsuccessful. “They keep giving us empty promises that never saw the light of the day,” he recalled.

SUBEB Reacts

Mohammed Abdullahi, Spokesperson of Bauchi State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB), said he needed permission from the board’s Executive Secretary before commenting on the state of Tsangaya Model Schools.

“It is either the board’s Executive Secretary (ES) or the Permanent Secretary who could grant you an interview on this matter; except for the ES directs me to respond.

“Give me some time to speak to him on the matter first to see whether he can talk to you about the issue or assign me to that,” he said.

However, the spokesperson did not respond days later. Falasa reached out to him again without success.

This report is produced with support from Civic Media Lab (CML).